The Greek booklet printed by Richard Pafraet of Deventer (1488): European Perspectives

Sabrina Corbellini and Margriet Hoogvliet

Situated in the east of the present-day Netherlands, the city of Deventer was during the later Middle Ages part of the Holy German Empire. Due to its membership of the Hanseatic network of trading cities, Deventer was able to participate in commercial exchanges with far-away cities as Cologne, Bremen, Lübeck, and Hamburg. In the seventeenth century this latter city would become an important European hub in the paper trade, printing business, international book trade, and news networks.

Deventer, however, could boast this achievement as early as the fifteenth century, with the oldest documented Dutch book shop (1458) in the Engestraat, owned by Wolter de Hoge, and no less than two active printers within its city walls. The inventory of the business stock of book seller Wolter de Hoge shows that he was mainly selling hand written books and woodcuts printed on paper broadsides, called “paper saints”.

The printing presses operated by Richard Pafraet (fl. c. 1477-1512) and Jacob van Breda (fl. c. 1485-1519) both had an impressive output, that surpassed the book production of most important European printing centres. Their printed books, with texts in Latin and in the Dutch vernacular, found local buyers, but were also transported to the west and south of the Low Countries, and to the west of present-day Germany. The huge number of paper sheets required for the output of the Deventer printing presses could not be resourced locally, but had to be imported, most likely via Cologne. This was, of course, facilitated by Deventer’s wide-reaching commercial and transport networks.

The northern Low Countries were by no means isolated from international intellectual developments. Rodolphus Agricola (1444-1485), originally from Baflo near Groningen in the north of the Netherlands, traveled for his studies to the University of Pavia, just south of Milan, and later to the Este court in Ferrara, where he became deeply imbued with Italian Humanist culture and became an expert in classical Greek. Agricola was certainly not the only Dutchman to study at an Italian university: “I have no hesitation in assuring you that if you come here, whatever effort you had to make to do so, you will say that it has well been worth the expense and it has brought you valuable rewards”, he wrote from Pavia to his friend Johannes Vredewold from Groningen in order to encourage him to take up university studies in Italy as well.

When Agricola traveled back to Groningen in 1479, he spent the autumn and winter months as a guest in the castle of ‘s Heerenberg. During this period, he befriended Alexander Hegius, then rector of the Latin School in nearby Emmerich. The two men would meet regularly in the house of the Brethren of the Common Life in Emmerich for lessons in Latin and Greek. When Hegius was appointed head of the Latin school in Deventer in 1483, he introduced there the Italian Humanist-inspired knowledge of classical languages obtained through the mediation of Agricola.

In Deventer, Hegius also collaborated with the printers who were based in this city, most notably with Richard Pafraet, in whose house he rented a room. Pafraet was inspired by the spirit of Italian Humanism as well, as he printed for example Plato’s Axiochus in a Latin translation by Agricola between 1483 and 1485. During the years preceding 1488, a period when he was less active as a printer, Pafraet probably traveled abroad in order to purchase Greek printing types. It is very likely that his destination was Venice, the city where the Greek teacher Manuel Chrysoloras was based initially, where an important Greek-speaking Byzantine migrant community was living, and where printers had started using Greek letter types as early as 1471 when Adam de Ambergau published Chrysoloras’ Greek grammar book Erotemata (Ἐρωτήματα).

Casting moveable letter types other than the Roman type and using these for printed books was a rare skill. The earliest printed editions with moveable type in Hebrew letters and with reading direction from the right to the left were made in Rome by Obadiah, Manasseh, and Benjamin of Rome between 1469 and 1473. There are currently some 153 printed editions in Hebrew letter type known from the fifteenth century. Later, towards the middle of the sixteenth century, one of the most prolific printers of Jewish books was Jacob Marcaria in Riva del Garda.

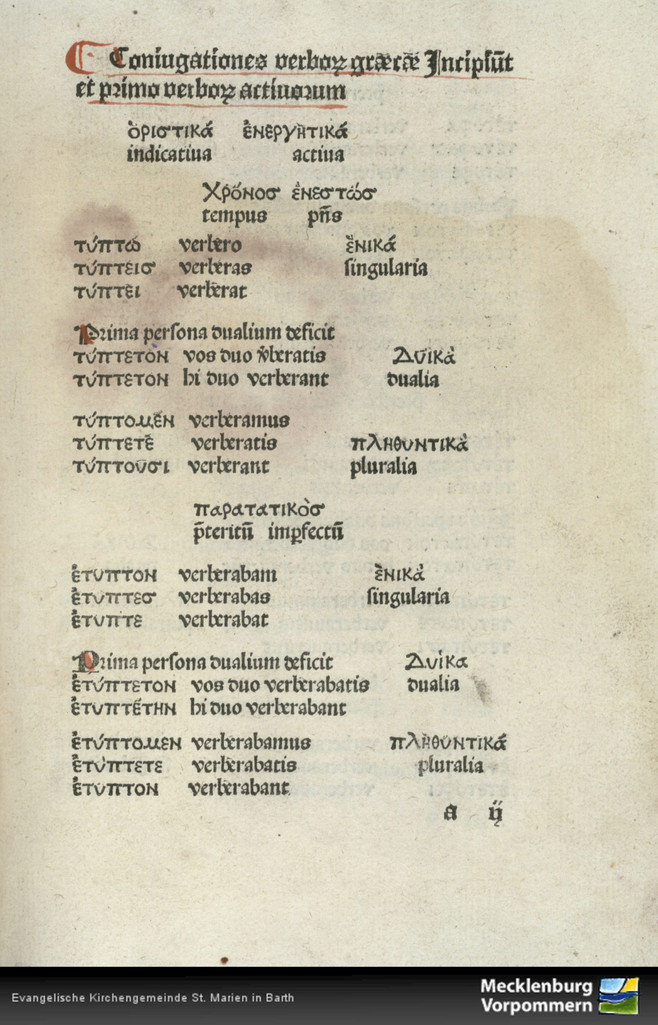

Shortly after his return to Deventer, Pafraet started using Greek letter types for Francesco Filelfo’s letters in Latin and Greek (1488), and for a small school book with conjugations of Greek verbs (Coniugationes verborum graecorum, 1488), most likely for use by the school boys of Hegius’ Latin school in Deventer. These two Deventer editions were the earliest prints in Greek outside Italy. In this manner, Rodolph Agricola from Groningen and Alexander Hegius, together with the printer Richard Pafraet from Deventer became important mediators of Italian Humanist culture in northern Europe.

Illustration: Coniugationes verborum graecorum barytonorum, [Deventer: Richard Pafraet, before 12 Dec. 1488], the digital collections of the Universitätsbibliothek Greifswald for the Kirchenbibliothek Barth.

Back to News